The casebook of Song Ci. The first forensic entomologist.

Karen Collins

Avid readers of crime fiction will be familiar with the ‘little grey cells’ of Hercule Poirot and Sherlock Holmes’ examination of trace evidence, both of which lead to the conviction of many fictional criminals. Less well known, if at all, is Song Ci, whose casebook ‘Washing Away of Wrongs’ provided coroners with a step-by-step guide to autopsy and forensic investigation. Why is his work so significant?

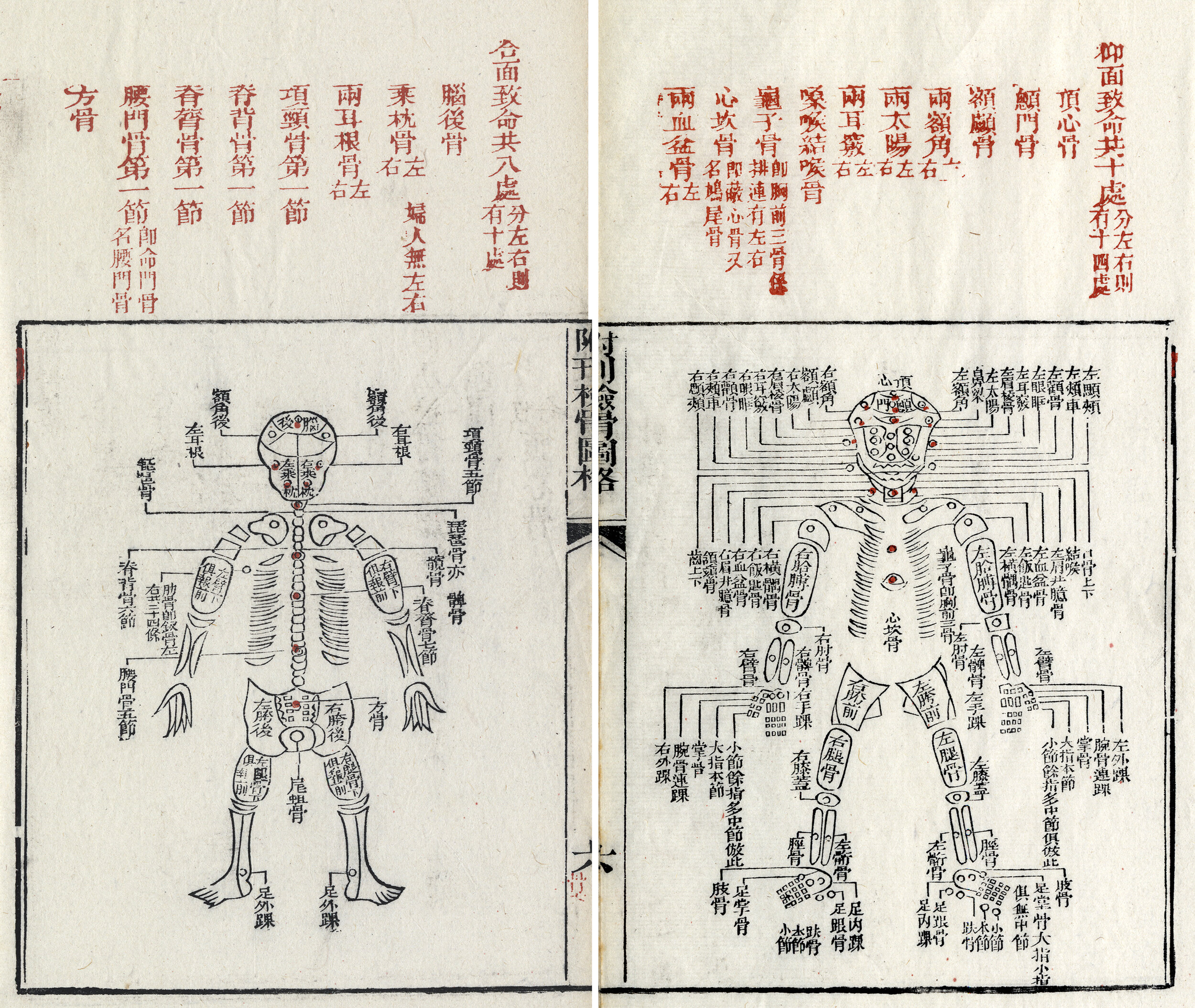

Nomenclature of human bones in Sòng Cí: Xǐ-yuān lù jí-zhèng, edited by Ruǎn Qíxīn (1843)

Unlike Holmes and Poirot, Song Ci was a real person, a Chinese judge who lived over 700 years ago and personally examined the crime scenes of physical assaults or difficult murders. His book, published in 1247, explains how to determine which wound was the cause of death, distinguish between ante-mortem and post-mortem injuries and differentiate between accidental death and homicide. It contains both his own experiences and those of others, includes case studies as examples of good practice, and was written to help avoid miscarriages of justice.

Perhaps most significantly, the ‘Washing Away of Wrongs’, or ‘Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified’, contains the first recorded use of forensic entomology as a means of identifying the perpetrator of a crime. Let’s take a look at the case.

In 1235 a peasant was hacked to death in a rural village. By testing different types of blade on a carcass it was established that the peasant was killed with a sickle. The choice of weapon suggested another peasant committed the crime. After initial questioning proved unfruitful, the suspects were asked to line up, place their sickles on the ground and step back. They waited. After a short while flies appeared and landed on one of the sickles, attracted by the traces of blood and tissue left on the blade. Faced with this evidence the owner of the tool confessed to the murder and was led away by the local magistrate.

Some elements of the text have dated less well, including the methods for restoring life found in book four:

“Where death resulted from seeing goblins...take the heart of a leek and thrust it up the nostrils (the left of a man, the right of a woman), about six or seven inches; cause the eyes to open and the blood to flow, and life will be restored.”

Never mind the goblins, who knows what disaster would befall the victim should we place the leek up the wrong nostril. You will be pleased to hear that leeks have many uses, including curing nightmares. Alternatively Song Ci suggests:

“In cases of nightmare, do not at once bring a light, or going near call out hastily to the person, but bite his heel or big toe and gently utter his name. Also spit on his face and give him ginger tea to drink; he will then recover.”

I think I would have nightmares about being treated for nightmares after that! Medicine and scientific understanding have obviously moved on significantly since 1247, there are no leeks in a modern forensic pathologist’s bag. I believe Poirot would approve of Song Ci’s advice to ‘regard nothing as unimportant’ however, and many of the systems and processes covered in the text would be recognisable to today’s forensic scientists.

“When the murdered man saw his slayer about to strike him with a knife, he naturally stretched forth his hand to ward off the blow; on his hand therefore, there will be a wound. If, however, the murderer struck him in some fleshy vital part and killed him with one blow, he will have no wound on his hand, but the death-wound will be severe.”

Right I am off to ferret around the casebook for another Song Ci-ism, see you there?

For more information about forensic science listen to our episode about Silent Witness.